It may be that the reader will not sound the name of Clay Johnson, but Johnson deserves a prominent place in the world of politics. Interestingly, not because of his political activities, but because he was one of the co-founders of the firm Blue State Digital, an agency that created and managed the Obama brand in the social networks during the presidential elections of 2008.

It may be that the reader will not sound the name of Clay Johnson, but Johnson deserves a prominent place in the world of politics. Interestingly, not because of his political activities, but because he was one of the co-founders of the firm Blue State Digital, an agency that created and managed the Obama brand in the social networks during the presidential elections of 2008.

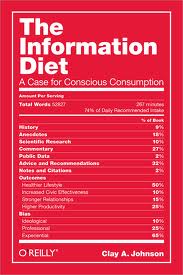

Johnson returned this year to the first line of the today of Internet by the publication of his book, The information diet. In it, Johnson encourages us to maintain a healthier relationship with the information that we consume on the Internet, showing the dangers of indiscriminate consumption of information. And to do so, Johnson provides us with a few skilled tips for establishing a conscious consumption of information.

The information diet is based on a parallel between the food industry and the content industry (or the media). Agriculture underwent dramatic changes in the TWENTIETH century, passing of the agriculture carried out by people in small plantations, the intensive exploitation thanks to the industrialization. The process of mechanization of agriculture allowed us to produce more by reducing the price, but at the expense of reducing the quality of the food and, consequently, the quality of our food. Obesity has become a real epidemic in developed countries, given the availability of manufactured foods rich in fat and sugars.

But, why consume these foods, even if we know they are harmful? The obvious answer is because we love them. Thus, the food industry in a certain way does not give us any but those foods that we, ourselves, demand.

With the content industry something similar happens, according to Johnson. Most of the big telecommunications corporations are anything but objective in the content that is presented to us. Although the true ideological positioning can go from the subtle to the openly brazen, it is certain that it influences the content that is presented to us, and in the way we treat them.

However, while the majority of analysts and media believe that these strategies respond to an attempt to establish the ideological agenda of a country or a region, Johnson argues that the media corporations only offer us the content that we demand.

The basis of this phenomenon is our tendency to seek information that confirms our beliefs, the well-known confirmation bias. The media used the information that we want (or tend to) consume as a way of maintaining an audience that is likely to result in economic benefit through advertising. And this vicious circle occurs not only in the traditional media, but also on the Internet, through the so-called farms of content (corporations whose purpose is to detect trends of content consumption on the Internet and provide news in line with these trends)

Food companies want to provide you with the most profitable food possible that will keep you eating it—and the result is our supermarket can cause self-filled with unimaginable ways to construct and consume corn. Media companies want to provide you with the most profitable information possible that will keep you tuned in, and the result is airwaves filled with fear and affirmation. Those are the things that keep the institutional shareholders that own these firms happy. (p 33)

And in the same way that we are what we eat, also we are what we look for in the Internet: the confirmation bias reinforces our previous beliefs, some of which may have no justification or support independent of, but to be simple prejudice. In short: a sure-fire way to deny the possibility of transforming the information into knowledge.

There were two ideas from the book of Johnson that give meaning to their whole argument. In the first place, unlike the other works on the influence of Internet in our lives, such as Nicholas Carr in Surface, Johnson does not blame directly to the new technologies of the dangers that these may bring, but our use of them. In the words of Johnson:

Blaming a medium or its creators for changing our minds and habits is like blaming food for making us fat. While it’s certainly true that all new developments create the need for new warnings—until there was fire, there wasn’t a rule to not put your hand in it—conspiracy theories wrongly take free will and choice out of the equation. (p 24)

And still Johnson:

Anthropomorphized computers and information technology cannot take responsibility for anything. The responsibility for healthy consumption lies with human technology, in the software of the mind. It must be shared between the content provider and the consumer, the people involved. (p. 24)

Secondly, this emphasis on personal responsibility and the way we consume information leads Johnson to proclaim that there is no such thing as the infoxicacion (“information overload”).

And is that the information does not ask us to eat, so that the problem is not the total amount of information, but our habits that lead us to consume information so compulsive and indiscriminate. In other words, the real problem is the excessive consumption of information (information overconsumption), so that we should think less about how to manage the information and more on how to consume it:

Information overload means somehow managing the intake of vast quantities of information in new and more efficient ways. Information overconsumption means we need to find new ways to be selective about our intake. […] In addition, the information overload community tends to rely on technical filters—the equivalent of trying to lose weight by rearranging the shelves in your refrigerator. Tools tends to amplify existing behavior. The mistaken concept of information overload distracts us from paying attention to behavioral changes. (p. 26)

Johnson, along with his reference to the food industry, puts a name to that lack of responsibility in the consumption of information: obesity information:

Our media companies aren’t neuroscientists, nor are they conspiratorial. There’s no elaborate plot aimed at driving Americans apart to play against each other in games of reds vs.. blues. A more pragmatic view is that our economy is organic. Through the tests of trial and error, our media companies have figured out what we want, and are giving it to us. It turns out, the more they give it to us, the more we want. It’s a self-reinforcing feedback loop. When we tell ourselves, and listen to, only what we want to hear, we can end up so far from reality that we start making poor decisions. […] The result is a public that’s being torn apart, only comfortable hearing the reality that’s unique to their particular tribe. It’s a new kind of ignorance epidemic: information obesity. (p. 54)

Three would be the forms which express the obesity information:

1. Agnotología, or questions that induced culturally: interestingly, it is not always true that more information on a topic is equivalent to a opinion more justified. Johnson cites the example of a study conducted on the perception of climate change: that people were more informed, they also were more skeptical about the reality of the phenomenon. It is not surprising, if we take into account that the media often present us different views of the same phenomenon, even though in reality there is, as in the case of climate change, a unanimous consensus among the communities of experts on its causes and possible consequences.

2. Closing epistemic: an immediate consequence of the confirmation bias: the tendency to judge sources of information with which we disagree as unreliable or of dubious reputation.

3. Failure to filter (filter failure): an idea put forward by Eli Parisier in his book, The filter bubble, which refers to the automatic filters information from our networks and search engines, we offer custom information. This customization can deprive us of the opportunity of confronting our beliefs with other information outside of our immediate circles of contacts, or that have nothing to do with our habits of consumption and navigation of content on the Internet.

The symptoms of obesity and information literacy are both physical and cognitive, and social:

Sleep Apnea: according to Linda Stone, the reading of emails and the attention to the updates of the social networks are causing an irregularity in our respiratory rates and heart.

Loss of sense of time: surely related to the effects that dopamine, released through various activities in the network, occurs in our brain.

Fatigue, attentional: the services of the web 2.0 are often qualified as technologies of disruption, given the constant care that we require for alerts and new updates to our contacts.

Loss of range social: the biases can lead to lessen the interaction with those people with whom we disagree on certain issues, even if they may enrich our perspective on other issues.

Sense of reality distorted: as in the example of the perception of climate change cited above.

Brand loyalty: a phenomenon to be sought and desired actively by the gurus of marketing 2.0 by using different strategies that seek to achieve the link from the customer to the brand.

Thus, responsible consumption of information can have great benefits in our lives at different levels. How to conduct an information diet effective?: although the response has to be different in function of the situation of each person, Johnson proposes a strategy based on three axes:

The first axis, we have the information literacy that includes the skills of searching, filtering, and processing, production, and synthesis of the information.

In the second place, the conscious regulation of our processes of attention. Johnson mentions software tools that we can use to control our sailing times and attention to certain services, we may allow you to make to optimize our connection sessions to the Internet, as well as applications that suppress the notifications of our social networks (which are a factor of scattering of attention). In the web page of the book, Johnson offers us an interesting list of tools.

In the third place, it would find the activities of responsible consumption of information, which could be summarized in:

Reduction in the number of channels of information to which we have potential access (for example, cable television services).

Planning of our browsing sessions, including approximate times of connection for each task.

Consumption of local news, for two reasons: first, because it is more likely that the information has not gone through the intermediaries of the great groups of communication; second, because among these news items may have important issues that can be solved with the involvement of local communities.

Avoidance of active advertising, whether by subscribing to channels of quality content that do not include advertising, or through the use of applications software that allow the removal of ads from a web page.

Diversification of the sources of information, including the conscious choice of contacts in our social networks.

In short: the book of Johnson is a reading highly recommended for all those of us who care about the consumption of information in our societies, and represents a fresh vision, and above all practical, on-the infoxication.