By Patricia Rivero

.

Long time ago, many institutions and organizations are concerned by the use of language around gender. There are expressions (spoken or written) that have historically positioned women in an inferior position to male domination. We have several examples of agencies working in this task: observatories of equality, research groups in universities, professional associations, public administrations, etc., Is a big step and a conquest of social awareness expand estascampañas to raise awareness about gender inequality. On the other hand, it is also true that gender inequality comes from a long time, and that immigration, rather, is a relatively new phenomenon. But some of those who study the phenomenon of immigration miss the achievement of initiatives on the same issue, but putting the accent in this case the inequality for ethnic reasons.

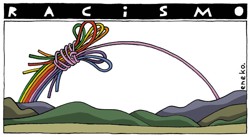

Now, let us reflect: how we use language to talk about immigration? Are we facing a situation similar to that of gender inequality? Is it also necessary to “make campaign” to eradicate some of the expressions/terms and uses of language that can have dyes racist and xenophobic? Far from raising controversy, I just want to invite the reader to reflect and think between all of us so serious, if we are faced with an analytical framework similar to that of gender inequality, but in this case, as I have already said, without awareness-raising campaigns and, without even awareness that we are entering a dynamic “them/us” is perverse.

I must say that the uses of the language around immigration are highly standardized in numerous areas of society, both within academia, as well as in the public administrations, the media and, as not, and in consequence, in the popular expressions. Such expressions, used by these social actors, they are so naturalized that there are poses that can be used harmful (harmful in the sense of identifying it within the mental structure “us/them”).

The problem is not the existence of a word or concept in itself, but the systematic use of each of these terms, and thus their naturalization. It is “normal” to say nouvingut (newly arrived, in Spanish), it is normal to say societat d acollida (host society, in Spanish), it is normal to say casa nostra (our house, in Spanish), it is normal to sayillegal, etc, a Lot of analysis about immigration have repeatedly denounced the excessive linking of immigration with crime. Obviously, there are to report it, this speech is a fallacy, aside from being xénofobo and racist, but do not have also the echo and denounce the link between immigration and integration? No, no one questions this excessive insistence on linking the two concepts. As well as the word rain is associated with water, the integration is with immigration. The word integration comes to say something like: “you are sick and you have to integrate yourself to us that we are a healthy society”.

With all that being said, I will try to deconstruct some of the terms that people (many times without distinction of class, gender, age and origin), we tend to use with frequency when talking about immigration. When we express ourselves, either verbally or in writing, there is the tendency to use expressions that often do not have their origin in racism is explicit and deliberate, but that these expressions are in the language of a subtle way, almost invisible, but that, according to some authors such as Van Dijk (2003) that behavior does not stop framed in a certain racism. In this sense, it is appropriate to take the idea of “racism everyday” that we proposed to this author in his work on Racism and discourse of the elites. For him, racism is not only about the ideologies of racial supremacy of whites (in our case better say “indigenous”) of any ethnic group, nor in the execution of acts of discrimination and aggression to be obvious or blatant, which are the modalities of racism understood at present during an informal conversation, in the media or in the greater part of the social sciences. Racism, for Van Dijk, it also includes the opinions, attitudes and ideologies of everyday, mundane, negative, and acts seemingly subtle and other conditions that discriminate against the minorities, that is to say, all the acts and social concepts, processes, structures, or institutions that directly or indirectly contribute to the dominance of the sector “natives” and to the subordination of minorities [1]. In this sense, it understands racism as “etnicismo”. We understand, in this way, that racism and xenophobia constitute a system of social inequality based on any attribute to ethnicity (religion, language, nationality, country of origin, skin color, etc) and within this, identify various discriminatory social practices, including discourse, which again are reproduced.

But, in what way can identify with these discourses impregnated attributes ethnic? Is it possible to identify them from what is called by Van Dijk as “racism everyday”?

Before that nothing was to clarify that the ways in which the discourse or certain terminologies [2] may occur, are different; namely, conversation, academic texts and school, the media, scientific texts or speeches issued by experts, laws, parliamentary debates, meetings of these bodies, lessons in schools, job interviews, etc., But even we can identify hate speech within the migrant community itself, both of the people migrated, as the “expert” in immigration issues.

Let’s look at some examples of terms that fit with this discourse, and discriminatory based on attributes ethnic:

“Nouvinguts” (newcomer, in English): this Catalan expression is normalized within the academy, the media and the public administrations. In the Spanish translation is not often used, so is only normalized its use in Catalan. The objection that we can make the use of this term is to ask: how do the foreigners, we arenouvinguts? When does an immigrant stop being a “newcomer”?. In addition to that, I think the concept makes it clear that we are speaking of a social condition. A German or a frenchman is never called nouvingut, but it is an ecuadorian, a peruvian, and a moroccan. Despite the fact that the italians are the nationalities most numerous in Catalonia, they were never callednouvinguts. Everything indicates that the label of nouvinguts is used only for those people coming from poor countries or in the developing world.

“Societat d acollida” (host society, in English): another expression that is commonly used both in academia and in the media, and the public administrations. There is some other justification on the part of the expert community in the choice of this term. For example, such expression is preferable in place of the “society of receiving” because it expresses the conviction of the importance of the bidirectionality and the active role of the society in connection with the “integration” of the immigrant. Particularly, I says that it is an expression of a paternalistic to the immigrant. In this sense, the Spanish Royal Academy defines the word “foster” as: “Welcome or hospitality that offers a person or a place.” While the word “welcome” is defined as: “one person Said: Support in your home or company to anyone.” Many thinkers concerned with social inequality have said that charity does not do away with inequalities, then why better not to think about that “bi-directionality” that is so crying out for a part of the society could be through other mechanisms (what institutional?), as for example an aliens act that is not criminalizadora and discriminatory.

“Casa nostra”(our house, in Spanish): the expressions that I consider the most evil. It has some characteristics similar to those of host society,such as paternalism. Once more we find an expression that sounds like a gift. On the other hand, casa nostrais a perfect indicator to show the relationship of us/them; and makes it clear that “this is my house,” and that “your (immigrant) you are a guest”. How do we ask the immigrant who “integrate” and be part of society if we are granting the status of a guest undefined?

In sum, we hope that some day the migrants to conquer the battle of the language in the fight against ethnic inequality, as well as did the feminists in their struggle for gender inequality. Yes, hopefully we will not have to wait centuries, as did the feminists.

.

Patricia Rivero July 1, 2012 Article published in LibreRed and in The cave, and sociological————————————-

Notes:

[1] Van Dijk, T. (2003): “Racism and discourse of the elites”.Barcelona: Gedisa.

[2] In this text I speak of discourse as synonymous with “term” and “expression”. Although análiticamente are different things, in this case I use it to refer to the same thing.